|

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The World According to OrvilleA Dogged Utopian Maps Out the City of the FutureBy Anne Fadiman, Life Magazine, September 1987; photo by Barbara Walz, Onyx

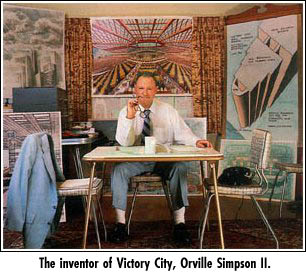

Simpson is 64 years old, and for the last 27 years his life has been devoted almost entirely to the planning of Victory City. He hopes that his designs for the Water Pik® booths, along with his designs for the elevators, cafeterias, sewage disposal plants, farms, schools, factories, golf courses and zoos, will some day be exhibited in the first Victory City's Museum of Science and Technology, which he hopes will be built in his lifetime. In the interim, hundreds of drawings are somewhat haphazardly displayed all over the furniture in his bachelor apartment in Cincinnati. Whenever he meets a stranger, he says, "My name's Orville, and I'm planning the city of the future." If the buttonholee evinces the faintest degree of interest, Simpson produces a set of small drawings from his breast pocket, and in a slow, patient, methodical voice, starts to explain, perhaps for the thousandth time, how Victory City is going to bring prosperity and happiness to the human race — if people would only listen.

When I rang Simpson's doorbell, he wasted no time getting to the point. "Would you like to see our cafeteria?" he asked. When I said I would, his face, which is broad and well scrubbed and utterly guileless, pinkened with eagerness. "There it is," he said, pointing to a drawing of a vast, skylighted room in which thousands of people (all conservatively dressed and Caucasian) sit eating at long tables. On the walls surrounding them is a series of murals that depict cavorting dinosaurs. "As we eat," said Simpson, "we will be able to study the history of evolution. That way we get two experiences for the price of one." The rendering was remarkably detailed. When I asked Simpson how long it had taken him to draw it, he said, smiling, "Two years, two and a half months. I do things slowly." Victory City has thus far been more than half a century in gestation. Its conception dates to 1936, when Simpson, age 13, lay in his boarding school infirmary, recovering from a rash. He was not a happy child. His father, an inventor, and his mother, a socialite, paid him little attention. He had few friends. He was failing most of his courses. Lying in his bed, itchy and bored, he found himself thinking about the Cincinnati slums that the Roosevelt administration had begun to raze and wondering what would replace them. A vision of a great city, housed in a single edifice as high as the Empire State Building, presented itself to his imagination. It would represent the victory of efficiency over inefficiency, wealth over squalor, progress over stagnation. He drew a picture of it. It looked like a castle. He told no one about it, afraid his parents would be uninterested and his classmates would laugh. Simpson never graduated from high school. He served as a private in the Second World War and then held a series of 23 jobs during the next 16 years He was a storm window salesman, a drill press operator, a cloth cutter, a foundry timekeeper, a Fuller Brush salesman. He kept a scrupulous record of his work history, with "Reasons for Leaving" charted in the right-hand column: Fired. Fired. Laid off. Fired. Fired. Quite, no sales. Fired. "I was always too slow," he explains. In the late '50s he used his savings and a bank loan to purchase two small apartment buildings, discovered that he had some talent as a manager and never worked a regular job again. […] During the '40s and '50s Simpson found his thoughts returning often to Victory City. "I could see the countryside turning into ugly subdivisions," he says. "I knew the only way to save the land was to concentrate the population in one place, with farmland all around it." Without knowing anything about modern city planning, Simpson had reached the same conclusions about high-density, environmentally conscious housing as LeCorbusier, Paolo Soleri, Antonio Sant'Elia and other well-known architects. In 1960 he started sketching. In the foreground of one of his early drawings, a huge concrete monolith surrounded by lush gardens, there is a small group of people. When I asked who they were, he said, "There's Doris McDonough on the right. She's a former neighbor of mine. There's the son and daughter of my electrician, and there's Irmgard Kersten, the girl I wanted to marry. Her hair looked like spun gold, and her eyes were as blue as … well, shall we say the sky?" Without embarrassment, Simpson recounted the story of how he had met Irmgard, who was then 19, when he was stationed in her village in Saxony for three weeks in 1945. They corresponded after the war, but it was not until 1959 that he decided he was financially secure enough to ask for her hand in marriage. Instead, he received a letter from her husband, a professor, politely explaining that Simpson was too late. "I've dated other women," Simpson told me matter-of-factly, "but Irmgard was too important for me ever to be serious about anyone else." Simpson has never made the connection himself, but it is perhaps no accident that his work on Victory City began almost immediately after this great disappointment. Though he had never had any architectural training, he started spending up to eight hours a day drafting elevations and floor plans. Sometimes an idea would come to him in the middle of the night, and he would sit in his bathrobe at a folding table he had bought with trading stamps, drawing until dawn. He wrote a 37-page, single-spaced, indexed manuscript titled "Orville Simpson II Presents Victory City, the City of the Future," which explained Victory City's housing, health, education, security, banking and insurance systems. A careful reading of this prospectus reveals a number of parallels between the neat, orderly life of a Victory City resident and the neat, orderly life of Orville Simpson II. Simpson eats most of his meals at a cafeteria. Victory City residents eat all their meals in a cafeteria. Simpson is allergic to dust, lint and cats. Victory City is decorated with elaborate floor mosaics instead of rugs, and cats are banished to a distant Pet Park, where their owners may pay them visits. Most striking, the seven pages of financial comparisons between Victory City and Old Obsolete City (Victory comes out ahead in everything from termite extermination costs to dental bills) reflect the fact that, despite his affluence, Simpson is, as he puts it, "as tight as a clam." He hoards string, rubber bands and old envelopes. His socks are all white, so when one wears out he does not have to discard its mate. His glasses come from Woolworth's. He is saving his money for Victory City, where he would like to finish his days in a penthouse apartment overlooking the gardens. He hopes to persuade a major corporation or developer to sponsor the project in a location of the backer's choosing. Failing that, Simpson has set up a foundation to invest his estate after his death so that construction may proceed as soon as the interest has sufficiently accumulated. […] For several years, Orville Simpson II has had a semi-official relationship with the architecture department at the University of Cincinnati. Students work for him part-time doing drawings of Victory City. This year he sponsored a competition, with $4,000 in prizes, for the best original design for a utopian City of the Future. Two of the competitors recently visited Simpson's apartment to show him their entries. The first student brought a large and complicated drawing labeled "The City of Tomorrow." "The energy in my city is generated by the thermal differential of the sea water," he explained, "and the elevator chutes run on superconductors." "Well," said Simpson goodnaturedly, "I don't understand a word of that, but good luck. You're young. You've got the rest of your life to work it out." "My city is more, well, psychological," said the second student. "It's designed to help people release their basic instincts. The walls of the city represent the unconscious, and at each gate there is a place for ridding yourself of a repression. Where that tree is, that's where you can urinate in public. Where that phallic spire is, you can have sex. Where that little pink pig is, you can slaughter animals to work out your aggressions." Simpson looked momentarily nonplussed. "That's … very interesting," he said dubiously. Then he put his arm around the student's shoulders and gently steered him toward a pile of his own drawings. "But let me show you another kind of city. I call it Victory City, and I'd like to tell you why." The next morning, I asked the director of the architecture department, a former Cambridge don named John Meunier, what he thought of Simpson. "When I first met Orville," he said, "I thought him a bit simpleminded. Nw I take him quite seriously, not as an architect but as a utopian. He stands squarely in the tradition of Thomas More and Charles Fourier, which is all the more remarkable because he's never read them. His vision is so completely worked out that it is almost totalitarian, but nonetheless, he's found an eloquent way to express his dreams. Whether or not they ever come true depends on how well they coincide with the popular consciousness." That afternoon, Simpson invited me to lunch at the Cambridge Inn Cafeteria, where he has eaten nearly every day for 15 years. He ordered the Senior's Platter (half price), folded his paper napkin in his pocket so he could reuse it at dinner, and requested a takeout container for his corn bread so he could have a free snack later that afternoon. We were the last people in the cafeteria, and Simpson invited the cashier, a heavy, middle-aged woman in a green apron, to join us. She looked tired and distracted as she picked at her meatloaf. "Shirley knows all about Victory City," explained Simpson. "She's been hearing about it for years. So what do you think, Shirley? Would you like to live in a place with no crime and no pollution, where you'll have to work only six hours a day? Shall we put you on the waiting list?" Shirley rested her fork on the plastic tray. "You know what I think, Orville," she said. "I think it sounds like heaven." Copyright © 1998-2007 by Orville Simpson II All rights reserved. No part of this website, including page content, graphics or overall layout/design, may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of the author. |