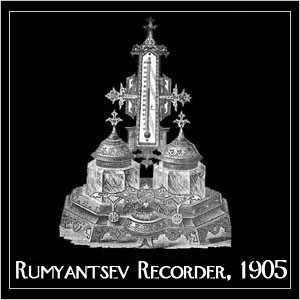

The Rumyantsev Recorder

The Archivist | November 15, 2007

The first years of the 20th century saw a peculiar fashion in the upper-classes of Imperial Russia, being a mania for elaborate mechanical clocks. Cuckoos were quickly outclasses by gold and silver songbirds of all varieties, as well as revolving princesses and dragons, deathsheads and plowsmen, pulley systems that raised and lowered jeweled suns and moons–in the pre-revolutionary world, time was a trophy to be displayed.

Afanasy Rumyantsev was the son of a modest but inventive toymaker in Novgorod who established a small shop in the capital shortly before being crushed to death by falling wine barrels. Afanasy had had an unhappy life in Novgorod, and by some reports impregnated a banker’s wife with extremely black hair, which forced their relocation. By 1902 he had taken over his father’s shop and conscripted the elder Rumyantsev’s intricate doll-faces and figurines into infinitely delicate clocks, becoming the premier purveyor of time in Moscow. He spoke to almost no one, but was obsessively passionate about his clocks, often visiting his customers to check on them during holidays. His most popular design was a clock which did not chime the hour, but played a small phonograph hidden in the mechanism, whose amplifying horn opened into a golden iris in the arms of a demon with carnelian feet and a swooning empress at his feet. The wax cylinder within played a charming, if slightly sinister melody, and the demon bent to kiss the empress every hour on the hour.

In exactly twelve of these civilized drawing rooms, the demoniac clock did not play its little song, but instead bellowed forth a scratchy, indistinct dialogue between an older man by the name Innokentiy and a young woman called Nadezhda:

My dearest Nadezhda Semyenovna, do not deny me. Meet me again in this place, at this time, so that I may swallow you whole.

Beneath Innokentiy’s voice the Kremlin carillon solemnly bonged out the hours. The demon bent to kiss his queen.

It cannot be ascertained how many of the recipients of Afanasy’s most special clock were kept awake with those voices in their hearts, but at least three put on their hats and gloves and travelled to the carillon the next day at the hour that tolled on the cylinder. They looked at each other surreptitiously, unwilling to question each other’s motives, but eventually one of them must have discovered the discreet red-tissued package tied to the base of a snowy streetlamp, and another small wax cylinder, which the trio hurried to insert into their demon-clocks and wait for the turn of the hour.

Again the ghostly voices, again the imploring Innokentiy, the reluctant Nadezhda. He promised her jewels and black arts and a throne of silver in exchange for her virtue, she insisted on her husband and her child, who lived in a great house in the country filled to the rafters with gold coins. Their voices were so plaintive and lifelike that the younger son of one of the fateful trio reported that his mother wept to hear the unfortunate Nadia in her travails. Distantly, behind their wretched voices, could be heard the doleful bells of the Novodevichy Convent. It seemed to go on and on, and they seemed unable to stop, unable to let the voices go, until one afternoon when they lost the trail or the demonic clockmaker lost interest, and there was no tissue-wrapped package below the bells at Kolmenskoe. They had no satisfaction: Nadezhda had succumbed only so far as to board the train with her suitor, but had turned back at the last moment. The same mother who wept to hear Nadia’s voice was reportedly inconsolable through the season and did not attend Mass for nearly a year, cradling her clock in her arms as she slept days and weeks into nothingness.

The three leisured souls had followed the story through Moscow high and low, collecting the wax cylinders as fast as Afanasy could pour paraffin into his molds. He kept them moving, running, every day, from clanging, hissing Kurskiy train station to sidewalk violinist with a cylinder in his open case. Much has been written on his motives, but it seems somewhat elegant to imagine that they were his clock, his revolving deathsheads and plowmen, pursuing Innokentiy, pursuing Nadezhda. He sat within his father’s shop, among the doll-faces and clock-gears and imagined them, running in circuits around his Moscow. He did not die until 1911, and so his reason for leaving the lovers forever stranded on a train platform remain his own. An earlier example of the alternate reality game is unlikely to surface.

[[Archive Group: Attic. Lockwords: Tether Systems, Operator Failure, Alternate Distribution Streams, Aristotelian Drive, Karolson Worlds, User Corruption, Mundus Infection. Last Accessed 9.001.6.7.21, UIN# (47)663.5-9]]

Comments are closed.

-->