Karolson & Hobshack

The Archivist | October 15, 2007

In 1879, a curious phenomenon arose among telegraph operators, especially among those assigned to non-essential traffic areas. It could be generally compared to the habitual, even compulsive playing of Solitaire or Minesweeper among modern office workers. What evolved was, as is often the case, far more difficult and complex than later, more technologically advanced iterations.

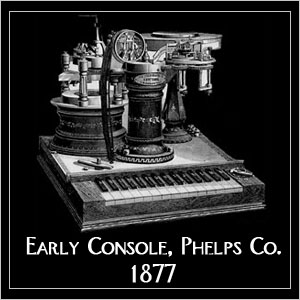

The Phelps Telegraph Machine (pictured) was at that time in widespread use throughout North America. Oskar Karolson, an operator in rural Ontario, a young-to-middling man of Jewish-Polish extraction with a love of puzzles, who taught the wheat farmers’ children mathematics and piano, had had a new Phelps delivered to his remote station sometime early in 1877. The telegraph traffic of dairymen and the odd dentist was low, however, and Oskar had little to do. In his boredom, he reached out across the wires.

Given the Phelps black key letters A-N, which is to say 3 vowels and 11 consonants as well as the fifteen white keys which sufficed for four essential punctuation marks, an execute command, four elements, four directions, and diurnal/nocturnal information, Karolson sent a now-famous message to an unseen counterpart in Chicago. Had the equally lonely Illinois telegraph operator been distracted, this missive would surely have been lost in the detritus of a metropolitan office, but luck was on the side of history.

The quiet telegraph upon which so much depended read as follows:

“I am alne. North–fire. South–water. East–earth. West–Air. Cme, fnd me. Execute.”

Curiously, when the corresponding Phelps Machine’s keys were depressed, a melancholy little melody emerged. The song echoed through Baxter Hobshack’s office, and through trial and error, the asthmatic operator managed to return:

“I am cming. Head East in the evening.”

Thus began the game of Karolson and Hobshack, in which Hobshack was led through a simple, charming world of Karolson’s imagination. Slowly, Oskar taught his friend a vocabulary which allowed all manner of expression that the simple commands could not alone indicate. East came to stand not only for the direction, but for child, mountain, gold ring, sparrow, ambush, and so on. Karolson’s code was whimsical and seemingly random, designed only to allow Hobshack to encounter the dairymen’s sons and dentist’s daughters of Ontario metamorphosed into magical children with rings on their fingers that led the Chicago man further and further into an invisible world of mountains and forests and battles.

Baxter Hobshack, sickly since he was a child, died of pneumonia in 1882. Karolson was devasated, not at first understanding that the telegraph he received, “Bax died in hospital May 4. Stop.” was not simply a new gambit in their old game. Through the wires he sent an orchard-owner’s daughter transfigured by a bicuspid helmet and granny smith spear to lure him from the “land of the dead” (indicated by the phrase “nightnorth”) in which Karolson assumed Hobshack imagined himself sorely lost.

He did not receive an answer.

Eventually, Karolson reached out again, and again. His primitive text adventure would expand through the network of American, and later British, telegraph operators, becoming the first known massively multiplayer game.

[[Archive Group: Attic. Lockwords: Karolson Worlds, Aristotelian Drive, Ur-Net.

Last Accessed 9.001.6.7.7, UIN# (47)663.5-9]]

Comments are closed.

-->